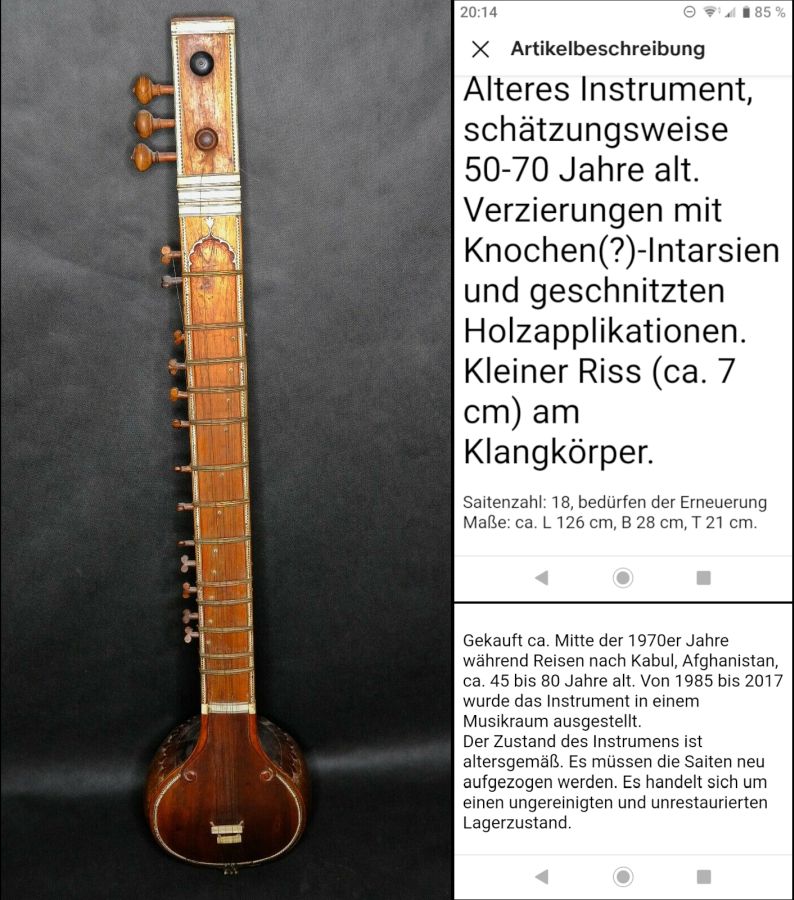

In April 2020, Matyas Wolter stumbled upon some very old Indian musical instruments for sale on ebay in southern Germany. His eye fell on one of them. The description indicated that the instrument was bought in Kabul, Afghanistan, in the mid-1970s. At that time it was already considered old, the seller told him. It was a part of a small local museum in southern Germany from 1985-2017.

The sitar was nicknamed Kabul sitar. It is probably +/- 110 years old…

There was a small crack (about 7cm) in the neck and the strings would have to be replaced. ‘It is in an uncleaned and unrestored storage condition’ reads the description.

In May 2023, the Kabul sitar arrived here in my shop, along with the Ilyas Khan sitar I previously restored for Matyas .

It soon turned out that it did have more going on than the original description indicated.

Besides the small crack and the old worn strings, it also turned out that the neck was well bent. At least 4 frets were missing and most of the tuning pegs needed a lot of attention. The bridges also had to be renewed.

In this section, I describe the work on the body. Mainly woodwork, in other words. In the next part, the metal fittings, the bridges and finishing and tuning will be covered.

We start with the body. The neck is noticeably well warped. This is easy to see when all the hardware is removed. So it needs to be opened up and straightened again.

There was already a crack in the neck, just on the line of separation between the 2 parts of the neck, and so opening it up goes pretty smoothly. The glue is very old and breaks easily. Still, the job has to be done very carefully. It is a very fragile instrument.

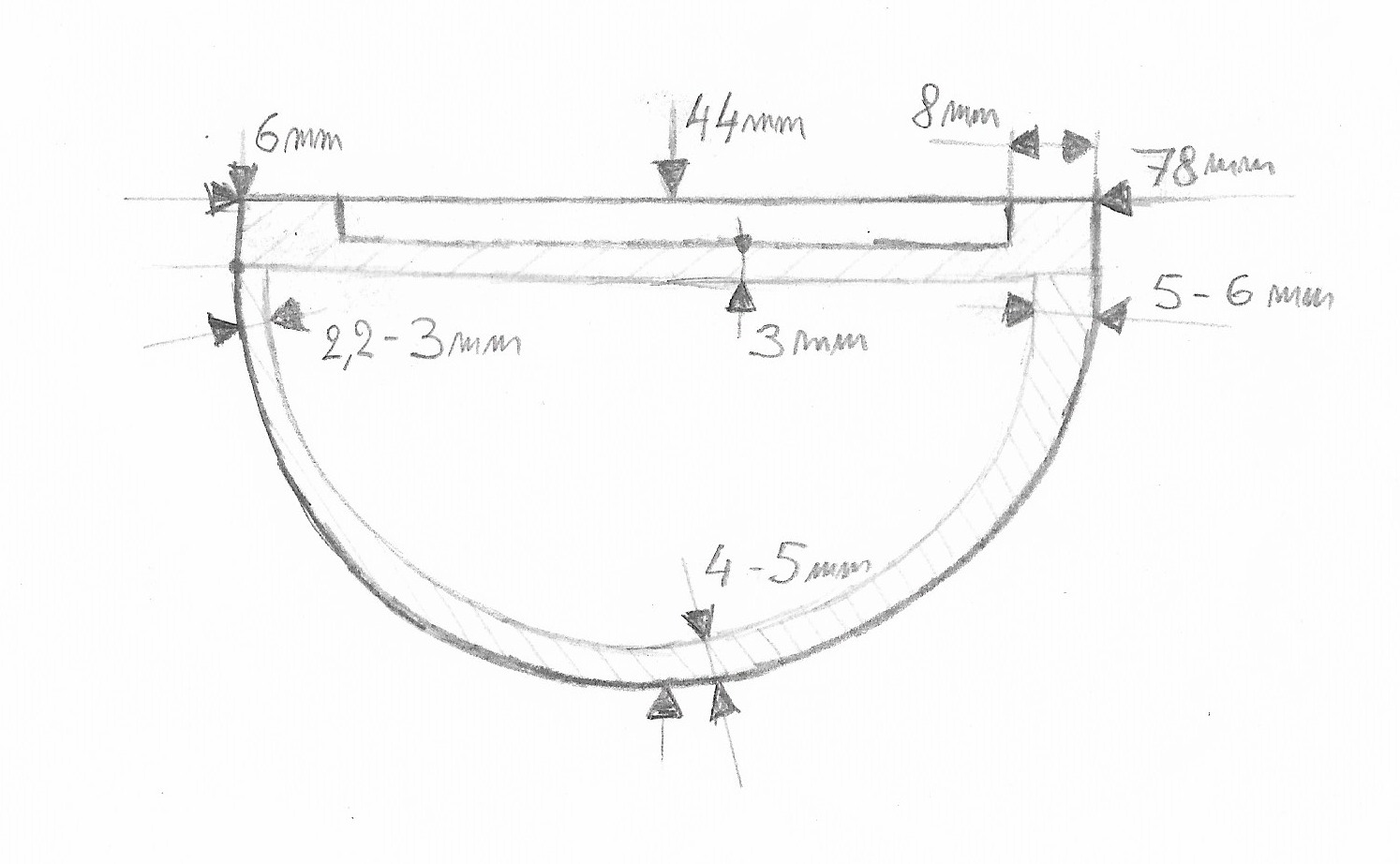

And yes, once opened there are a few striking things to see. The neck is made extremely thin, and the lower, round, part has an unusual thickness gradient. The front, which holds the tuning knobs, has a thickness of 5 to 6 mm and tapers to a thin 2.2 to 3 mm on the other side. The top flat plate is only 3 to 4 mm thick.

I also note that there are very small holes in the wood of the neck, most likely cavities of woodworms. There is no trace of the worms themselves, fortunately, and the damage does not seem to be too bad.

I also notice an additional crack in the side of the neck. This could not be seen on the outside, but it has certainly weakened the neck well. Now that the neck is open, this is an excellent time to repair this crack properly.

Then the time has come to close the lid again. I leave a small signature and after a final look at the nevertheless finely flowing and evenly finished inside, the pieces go back together. Everything still fits perfectly.

After a few days of good drying, the heavy solid straight beam and ropes can come off and we get a perfectly straight neck again. The kabul sitar is on its way of return.

Then it’s the pegs’ turn. There are 8 main pegs on it for the main strings and 11 tarav pegs for the sympathetic strings. Of the 5 main pegs present, only 3 seem usable and 1 is missing. Of the 2 cikari pegs, only 1 is usable. We then start combining the good and usable pieces and use the head of the too-short one to make a new fitting one.

Then I dive into my box of old (discarded?) specimens and find 2 similar pieces whose head I can update. In this way, I put together a full, fitting set of large pegs. In the meantime, that looks good.

1 cikari peg I then have to replicate myself. I start again from an old scrapped peg, taken from a very old sitar from Bangladesh. After some sawing, filing and sanding, a nice new one emerges. I give it some dents and bumps and finish it so that it is indistinguishable from the others.

This is followed by checking the tarav pegs. It becomes a real puzzle because most of them are so worn that they keep coming loose and no longer fit. I then decide to combine these pegs with new internal bushings. See the previously demonstrated method here. All in all, it’s not too bad. I only need to replicate 1 new tarav peg. For that, see the same procedure as for the cikari pegs. The cikari pegs and tarav pegs are very similar, and in fact almost interchangeable. The only difference is the location of the hole where to attach the string. On the cikari pegs, it is outside the neck, and on the tarav pegs, that hole is on the area that is inside the neck.

So much for the first part. All wooden parts are complete and checked for proper functioning. The instrument is ready for the finishing phase. See part two on this Kabul sitar restoration soon.

Gorgeous restoration for this very unique and beautiful sitar dear Klaas! It will be awesome to play some old-style sitar gats on this antique piece.